2023 Harris County Regional Award Recipients

Search Writing Award Recipients

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Search Art Award Recipients

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

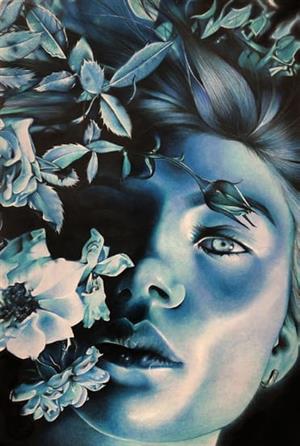

American Visions

-

April Wang—WINNER: AMERICAN VISIONS MEDAL

Verge

By APRIL WANG

Grade: 12

Kinder HSPVA, Houston ISD

Teacher: David Waddell

-

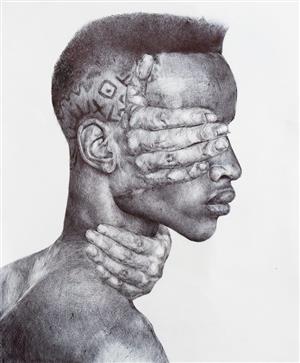

Jennifer Alexander

Propaganda

By JENNIFER ALEXANDER

Grade: 12

Westside HS, Houston ISD

Teacher: Susan Smith

-

Chloe Shao

Chain We Can Not See

By CHLOE SHAO

Grade: 9

Private Art School

Teacher: Ping Zhao

-

Ryan Qiu

Still Life of a Yellow Backpack

By RYAN QIU

Grade: 11

Private Art School

Teacher: Ben Xu

-

Manahil Ali

Perfectionist

By MANAHIL ALI

Grade: 11

Jordan High School, Katy ISD

Teacher: Hailey-Ann Booth

American Voices

-

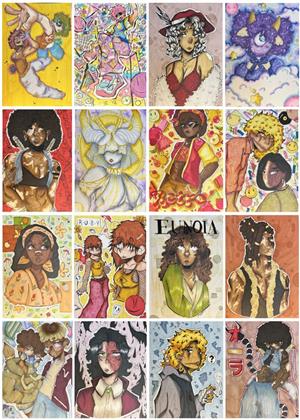

Kyra Ezikeuzor—WINNER: AMERICAN VOICES MEDAL

My Nigeria

By KYRA EZIKEUZOR

Grade: 10

St. Agnes Academy

Teacher: Herman Sutter

Get lost in the good food, Sweet morning air

Feeling feminine and strong A country pulsating

My cells vibrating

In tune with every particle Of My Nigeria

Life has meaning,

Nigeria is my meaning

A country manufactured by the British and colonized by my heart Breast and bone and blood

Aunty Ada’s sweet stew and yam

Igbo: A language I do not know yet rich on my tongue My Nigeria

Intelligence, strength, fortitude Flooding, kidnapping, corruption Family, insanity, Nollywood

Our Nigeria

1969

The Biafran War The air raid is silent

The starvation is loud The sky is but smoke The war over but

My father’s friend killed at the border An anti-federal Biafran soldier’s uniform Tucked away in his luggage

Your Nigeria

A gross blood clot Festered by the British For personal gain 1966 to 1969

An alien pogrom, ethnic cleansing, civil war Humanitarian crises, hundreds of thousands of Igbos Starving, dying

Children cauterized by famine

Mothers wailing, heads craned toward the heavens, petitioning to God Men at war, losing

Fighting, strong, and devoted to

The idea of Biafra, a new nation

A Red Cross banned, international aid banned By you, Nigeria

Corruption, devils, hatred, sin Vain politics, wealthy politicians A country not loving its people

A 2022 flooding; a million displaced A lacking infrastructure

The oil-rich hands of politicians Greased by pride, pockets padded With lovely money from richer countries His Nigeria

Family, intelligence, fortitude

The love of God permeating through music, heat, good food The architecture: carved from earth and mud-soaked hands Millennia of life before the British

Tribes of tunes and drums and rhythm

Loud weddings, fine garments, the Holy Family My Nigeria

Who am I if not the rhythm

The African zest, the spice, the zeal Infused in my blood?

Who am I if not the child of immigrants, brought to America for educational salvation? Who am I if not the Jollof rice that knows me more than I do?

Or the Udara fruit, sweet and tart and full of life? His. Her. Our. My Nigeria.

-

Jacqueline Xiong

Moonlight Sonata

By JACQUELINE XIONG

Grade: 10

Glenda Dawson High School, Pearland ISD

Teacher: Tianmei He

In the summer of my sixth grade, Lǎomā drove me to thirty-minute piano lessons in an ivy-clad brick house every Sunday. The drive to and from downtown was two hours in total, but my mom was unemployed back then, and I was never aware of how much time I occupied in her life. So it became a ritual of sorts for us to make the two-hour drive on Sunday afternoons, buckled into a sticky, itching kind of silence with our windows down and the August breeze streaming in.

That year was my fifth year spent in America. Before then I had spent a bright, happy childhood in the busy archives of Wuhan, sucking on Tanghulu and skipping rope between the crumbling buildings of my hometown. Then in the lapse of one summer, I had been shipped to cold, chilly Milwaukee— where the aunts and uncles who raised me were absent, and where I was introduced to my parents at last. My mother, Māmā, and my father, Bàba.

The terms of address had never stuck. From some point on, my parents had become Lǎobà and Lǎomā. Old father and old mother. They were not old at that time, but they were plain and common, unlike the powerful kings and beautiful queens who I’d envisioned as my nameless parents.

Five years later, my mom— who was not nameless now, but who was as foreign as a stranger all the same— rolled up the car windows and parked us near a Chinese bakery ten minutes from my piano school. The August sun was heatless but unwavering. I pushed open the car door and jumped out onto the melted concrete, two dollars balled in my sweaty palm. My mom tried to take my hand, but I slapped her hand away.

Like the two-hour drive, the bakery, too, was a ritual of ours. Maybe bribing me with egg tarts and pineapple cakes was the only way my mom could think of to make us less strangers. It had worked for a week or two, until last Sunday, out of the blue, she’d pulled to a stop near the bakery and tried to tell me a story.

The story was a true one that happened before my birth. It was about how my mom was planning to go abroad to college in Canada, and then she’d found out that she was pregnant with me, and after that she had to remain a jobless stay-at-home mom for my sake. I wanted to tell her that I didn’t really care about her life, but the story wasn’t over yet, and my mom was still talking about how Auntie Xue and Auntie Li had always hated her and raised me in China away from her. Like my aunties were evil villains, and she was just a poor princess from Andersen’s fairytales.

The story went on for a long time. The two dollars I carefully took out from my piggy bank every Sunday were beginning to turn gooey in my palms. I pried my fingers away and held the dollar bills up to the afternoon sunlight, and they were already drenched with sweat.

My mom asked, Are you listening?

I stuffed the money in my fist again and nodded. She said, I wish you could love me more.

I thought about how my aunties had warned me against my mom. Auntie Xue had taken me into her arms and said that my mom hadn’t meant to be absent in my childhood, of course. My mom only had to because she and my dad were too poor at the time, and if I wasn’t too careful with my future, I’d end up like her. But my mom was still a stranger. No amount of sweet buns would change that.

Are you listening? My mom said again.

She tried to take the dollar bills from my fist. I looked at her and saw that she had been crying— her face was blotchy and red and her eyes were watery, and princesses were much prettier than she was. I snatched my hand away from her and jumped out of the car. Behind me, my mom shouted something, but I was running toward the bakery, eager to buy an egg tart before the money disintegrated entirely.

Now, my mom didn’t try to hold onto me any longer. Even as I ran for the bakery, I could feel her eyes on me, uncomfortably heavy.

***

On the Friday my mom packed everything into a multi-compartment backpack and flew to upstate New York, there

was still one day left of my eighth-grade final exams. We were adapting to the drowsy humidity of Houston compared to the perpetual chill of Milwaukee, so when my dad burst into my room with the news at seven AM, I was still half- asleep, blissfully ignorant of what had happened two hours prior.

My dad had been the first to discover the departure. He’d woke up at four thirty to prepare for work, and when he pushed open his bedroom door, he’d come face to face with my mom. My mom was dressed for the northern weather. She had a black backpack over her shoulder and a plane ticket in her hand. She had been unemployed for years, so when my dad asked her where she was going, he thought she’d tell him that she was going for a job interview. My mom gave him a kiss on the cheek and said that she needed a break.

And on the last day of your final exams too,Auntie Xue said over Skype.She doesn’t care about you at all. My poor, poor sweetheart.

Uncle Xue said, Did she tell you that she was going to leave? No, I said. I had no idea.

My face was blank. My dad had gone off to work in a daze. Maybe I was stressed about my exams, which were starting in an hour. Maybe my mom was still a stranger to me.

Would you have stopped her if she told you?Auntie Li asked.

Yes, I said. Then, no.

Why not?

I still have exams to study for, I told her. She relaxed a little, told me to keep the Skype call open, and waved me away. I went to my room and closed the door. A slab of wood away, I could hear my aunts and uncles talking to each other in hushed voices. They had been muttering about my mom again last night, their voices just loud enough over the phone for her to hear. How temperamental, they said. What if she never comes back?

But even then, I knew that she would always come back.

***

When my mom was thirteen, my grandpa gave her a plastic keyboard for her birthday. Back in 1980s Wuhan, every little girl dreamed of hiring a Western piano teacher and dressing up for piano recitals in puffy white dresses. But even back then, grand pianos were a luxury, nothing an ordinary family would buy for a little girl’s silly dreams. So all my mom got was a 44-key plastic keyboard from the convenience store, a flimsy thing that scraped at your nails whenever you pressed down too hard.

Two months before the summer of my sixth grade, I’d fallen in love with the piano somehow— maybe it was a month of continual Piano Tiles or a recording of Étude Op. 25, No. 9 that sparked my own twenty-first-century pianist dreams. I dreamed of notes flowing like water from my fingertips, dreamed of storming through some furiously-paced sonata that ended in thunderous applause from a full hall of audiences in Carnegie Hall. My dad considered my dreams too insubstantial to purchase a full grand piano for; in the end, it was my mom who pursed her lips and lugged home a one-thousand-dollar electric piano on her own.

We had just arrived in Houston when I began to play piano again. I sat in front of the unboxed keyboard and played Piano Sonate op. 27-2 “Mondeschein”— the first movement of Beethoven’s famous Moonlight Sonata. I quit piano lessons after the summer of my sixth grade, and the electric piano had gathered dust for two years. The Moonlight Sonata ended up being the only sonata I learned well enough to play. Now, those two-hour drives to downtown Milwaukee seemed like years away.

That night, my mom asked over the phone whether I would like to continue lessons here in Houston. She was out getting Taco Bell for my dad after a long day of moving. I had already checked the map, and the nearest piano school was half an hour away, just enough time for her to tell me another story.

She heard something in my voice and said, a little snappishly, You’re too old for stories now.

I told her that I didn’t want to go to lessons, and even if I did, I was going to learn how to drive soon. I didn’t need her to drive me any longer.

My mom didn’t respond immediately. She pulled out of the Taco Bell line. I’m coming home. God, I’m so tired. Stupid moving all the way across the United States.

Can you bring something for me before you come home?I asked, but it wasn’t a question, not really. Only an expectation.

She was still unemployed. Over the international phone, my aunts and uncles still muttered about how she was useless, lazy, aging. My mom paused over our call and laughed under her breath. See, you’re like this again. Like what again?

You only call me when you need me. When you’re all grown up, you won’t need me anymore, and you won’t talk at all to me by then.

A lapse over the call. Static buzzing. I tried to think of something to say. At last I said, That’s not true.

I could hear a rustling as she shook her head on the other side. Do you know, she said. Do you know what your second uncle said to your dad about me on the phone last night?

I didn’t know what second uncle said. I had no idea who second uncle even was. What else could they say about my mom— this plain, no-income, unloved woman who demanded too much? Just what they usually say, I said. Just ignore him.

She laughed again. There was triumph in there, victory at being proven right. You think it’s easy to ignore something like that? He wanted your dad to divorce your mom, you know. He thinks your dad deserves better. Do you want a stepmom? A prettier, smarter stepmom who makes two hundred thousand dollars a year?

I stared down at my phone screen and said, You should divorce if you want to. There’s still you, she said.

I wouldn’t care, I said. It was meant to make her feel better. But from the other end, I heard the abrupt, faraway screeching of a car. Someone shouted, Watch where you’re going, fucker!

I waited until the sound of brakes was replaced by a long stretch of white highway noise. Well, she said at last. Well.

You’d be happy if I left?

I said, You should be happy too.

How selfless of you, she said, a little mockingly. She was thinking about all the times I had abandoned her; in the parking lot as I ran toward the Chinese bakery, in the waiting lounge as I greeted my piano teacher, in the four- walled living room as she argued with my aunts and uncles. Suddenly she asked, When was the last time you practiced piano?

I was practicing just before she called. She laughed. God, how proud you sound.

***

Thinking back, my mom wasn’t always this way. At some point, she didn’t complain about these two-hour Sunday drives. She didn’t cry when I never listened to her story, when my aunts and uncles muttered about her late at night, or when the piano she lugged home gathered dust. She didn’t object when we moved all the way across the United States and heaved three people’s belongings into a house that looked exactly like every other down the street. But sometime in the midst of all that, after giving without receiving too many times, we became more obligation than love. One time, even before my mom left, I ran away first. It was some hazy time in third or fourth grade when the April snow was just beginning to thaw. My mom was repeating what she always told me— I’m your mom. But this particular phrase that she always went back to, this phrase that seemed to contain the obligations of the world, I could care the least about.

That afternoon, I snuck out of the back door and ran as fast as I could. I crouched behind the hydrangea shrub next door and waited for my mom to burst out, turn on her car engine, and drive off to look for me. As soon as she left, I could run and run and never look back again.

At five or six PM, the sky was just beginning to darken. My mom stepped outside of our house and closed the door behind her. She didn’t turn on her car. Instead, she rolled out the old bicycle my grandpa gave to her on her eighteenth birthday, checked the brakes, and began to bike into the distance. No car keys, no backpack on her shoulders. Only her and her ever-lengthening silhouette, blurry and orange under the last rays of sunlight.

My legs aching and the rest of me feeling utterly stupid, I waited until she was gone, then stood up and returned to the unlocked house.

When she returned an hour later, none of us mentioned anything. My mom put dinner on the table and talked about how she heard someone playing the Moonlight Sonata today. That night, she gently looped the first movement of the sonata in the background as she searched for piano schools for me to go to next summer. Piano school would be the only thing she ever asked of me.

***

Lǎomā came home on a cloudy gray morning at the end of June. Everything was pretty much the same before and after her departure, so we slipped back into an effortless routine. I spent my summer days reading novels and playing the piano. My mom spent her days buying takeout for our family and searching for job applications she would never go to. We co-existed, two figurines in a fairytale music box, the Moonlight Sonata lilting softly alongside our movements.

Four days after her return, I was playing the first few bars of the second movement when I looked up to find her leaning against my bedroom door, nodding along.

When our gazes met, I was strangely relieved. I knew what she was going to say. It was like how I knew her stories were coming, but I didn’t hate this one.

My dad was out today. The international phone line was yet uninstalled. The newly familiar house was hushed and quiet around us. Outside, cicadas hummed as the summer breeze streamed in through the open window. It was not August, but it was summer again.

“How was New York?” I asked.

“Good. I saw my uncle— your great-uncle.”

“Was he nice?”

“Very.” She paused. “I missed your piano playing.”

“I play the same song every day,” I said. I wondered, briefly, whether she was going to say that she missed me. She shook her head, a little amused. “You only learned one song from three months of piano school.”

“I’m not a good pianist.”

“That’s fine. I wasn't training you to be the next Lang Lang or anything.”

She had no expectations for me now, I realized. My mom had no more dreams of piano recitals with puffy white dresses. Somehow that was unthinkable.

“I’m sorry,” I told her.

She looked at me upon that, almost surprised. She was going to say that it was fine. Then she changed her mind and said, “Me too.”

I shook my head. My mom stopped what I was going to say and said, “I’m going to start traveling when you go off to college. God, I hate the humidity of this place. I would much rather live in the countryside up north where we have fewer neighbors and more moon to look at. What do you think?”

“I think that’s nice,” I said. I did think so. “Okay,” she said. “Good.”

Two days before my mom packed everything into a multi-compartment backpack and flew to upstate New York, she sat me down on the molten asphalt outside our house. The May sun was heatless but unwavering overhead. Lǎomā handed me a pineapple bun and, instead of telling a story, told me a plan.

Her plan was this: two days later on Friday, the first day of June and the final day of my eighth-grade exams, she would take a 5 AM taxi that drove her all the way from our house to the George Bush Intercontinental. From there, she would take the earliest morning plane and land in upstate New York at noon, and by the time everyone else in our family heard about it, she would already be two thousand miles away. She would dwell in New York for a month or so, figuring out where she could go from there. She was tired of doing things, she said. She wanted to take a break and figure out her life.

There was relief on her face. Anticipation. She was telling me because I deserved to know. My mom looked at me and in the moment, under the May sun with a half-melted pineapple bun sitting on my palm, I knew that my mother would stay behind for me.

So all I said was, “Okay, Mom.”

Somewhere far away, the first movement of Piano Sonate op. 27-2 continued. The notes listed on, a perpetually unfinished song: A-D-F-A-D-F-A-D-F-A-D-F…

-

Vishnu Siripurapu

The Insight of Reality

By VISHNU SIRIPURAPU

Grade: 8

Adams Junior High School, Katy ISD

Teacher: Kim Crandall

Lost. The only word I have ever felt. Never a fit for society. Always an outcast.

Two minutes. That’s how long I have before the possibility of my vision coming back.

A possibility.

CLANK. The noise reverberates through me as the nurses raise up the rails on my gurney. The hospital clamors around me, rushing to other procedures, to save other lives. The voices drown out my own thoughts. Engulfing me into the chaos.

I lie on the stretcher while the nurses transport me to the procedure room, the wheels rolling on the smooth hospital floor. Being set down on the table, the cool touch of the metal stings my exposed spine while the sterile smell of the hospital seeps into my nose. I close my eyes when the harsh white light of the hospital flicks on, thinking back to the first hint of steely light outside that showed morning was on its way. The sunrise that appeared as a streak in the sky to my faulty eyes.

As the doctor walks in, he opens the drawer beside me, and pulls out the needle. “Ready? This won't hurt a bit,” he assures me, confident in his skill, pushing the syringe further into my spine. The cold needle tears through my frail skin, hitting a nerve. My legs are on fire; the world goes black.

My possibility vanishes into an unlikelihood.

***

I look through the cards laid out across my bed, each written with encouraging messages of: “Get well soon!” or “You’re so strong!” How could they know that when I’m the kid they ignore as I brush past them in the hallway? I exhale shakily, trying to catch my breath one more time before they come in to check my vitals. I wait patiently, watching the rain patter quietly on the windows of my room in rhythmic patterns. Looking up from my bed, I can make out the faint shapes of the farm close by where I fell. The doctors tell me I collapsed from a mosquito- borne disease, but all I can remember is being alone.

The nurse comes in, saying we need to start an IV. I grimace as she holds the needle steady, pressing on my skin. She plunges it in, and my body goes rigid when the fluids coarse through me. I grab onto the IV pole in front of me, grasping for a foothold as my head reels. Rolling it to the bed, I lay down to see the nurse beaming back at me. She wants to know how I got here. She pities the little boy in the hospital. Everybody does. Not in the mood to talk, I take the chance to rest my eyes before the doctors approach me with bad news. Or no news at all. But isn’t that the same?

“We’ll be monitoring you over the week, but as of right now we don’t see any effects of the virus in your body. At the earliest, you’ll be out of here by Friday,” the doctors exclaim as my parents sigh wearily of relief. But I can see the truth they’re hiding. They don't know what's wrong with me. No one does. Why can’t I be normal?

***

The blinding white lights of the hospital flicker above me. “You need to stay still!” The doctors clamor around me as I thrash around, trying to regain feeling. Of anything. I try to wiggle my toes, peering over the blank sheets to look at them, wishing I hadn’t. They lie cold and motionless on the hospital bed. I tell them to stop, tasting the bitter saltiness of the tears streaming down my face. I scream. Unable to move. Unable to feel.

***

I jolt awake to the blaring sound of my alarm. I rub the sleep out of my eyes as I stretch my arms before turning off the tedious clock by my bed. At once, I turn to the receiver next to me and dial the number written down. A shrill ring emits from the phone, cutting through the room for a moment before my parents hastily pick up, making me chuckle solemnly — when they speak, I can hear the sleepless nights behind their quivering voices. They’ve been worrying about me rather than taking care of themselves. I let them know I’m fine when in truth, I miss them and my sisters, wanting to feel the warmth of their love from the depths of the cold hospital. I hear the tension in the room as my dad speaks up with a clear edge in his tone. They’ve clearly argued about this before mentioning it to me. He manages to mutter what he meant to say,

“We won’t be able to come to see you tomorrow.” “Why not?” I retaliate, coming off as selfish.

“Your sisters got the flu, and we have to stay to take care of them.”

“Well why can't you bring them here?” I grasp at a solution, longing to see my family.

“We don’t want you to get sick before getting discharged from the hospital. But, we’ll visit as soon as they start to feel better,” they promise, hearing the desperation in my voice.

The call goes silent as I process the thought of being alone for the first time. Truly alone. I stare at the numbers on the dial, all of them blurring together. I rub the tears out of my eyes, and glance again only to find the hazy numbers. Looking up at the room, the painting on the wall became fuzzier, and the sky outside foggier. I quickly dismount the bed, picking a book off the shelf in the back of the room. I started to read. Only I can’t. The words became indistinct.

***

In the morning, I pace the room as the doctor comes in to check my labs again to ensure I can leave tomorrow with my parents. Just smile and pretend nothing’s wrongI think over and over, the words pounding inside of my head. As he’s leaving, the doctor explains any residing symptoms of the West Nile Virus I may have. I struggle to speak up when he goes over loss of vision, hoping for my facade to not be found out. For my parents’ sake. When he drops his pen, I reach to pick it up, grasping at the floor. Only, I scratch at the bare ground beneath me as he picks it up from behind me. I regain myself, keeping my story straight. I must not have seen the pen land over there. The doctor looks me straight in the eyes, articulating a chilling phrase. “What have you done?”

***

“One more time, just stay still,” the doctor orders as he sends the cold needle through my spine for the second time. The needle sends away my sense of self, my legs numb, my mind split, and my arms flailing for a hand to hold. A hand that isn’t there. I reach out, with a sense of want. A sense of need.

***

They rushed me to the procedure room, scheduling an emergent Spinal Tap. The doctors explain how they'll send a needle into my Spine three times to clear the Spinal Fluid build-up that’s keeping me from seeing. The procedure is said to be painless. But, the chance they hit a nerve and I may lose sensation in my body. A chance.

They stop me in front of the procedure room, transporting me onto the bed. Two minutes.

Two minutes for a possibility. A possibility.

***

I grimace in pain as they send the needle in one more time. I will feel pain one more time. I will reach out one more time. There will be no one there for me, one more time. One more time. The needle rips through my body, hitting my spine, sending shockwaves through my legs. My mind draws a blank as the last thing I see is the blinding white of the hospital in front of me. The once sterile smell seeps into my nostrils. The cool touch of the table stings my exposed back. The world goes black. Engulfing me into the chaos.

***

I wake up in my familiar room at the hospital with my parents beside me, holding my hand. They tell me the procedure went well, and that they’re here for me. But, I can see past their warmth and love to see the sleepless nights behind their wrinkling eyes. I tell them to get something to eat at the cafeteria, promising them to rest. As they leave the room, I grimace, grabbing onto the IV pole to steady myself. I grab the same book off the shelf, the words no longer indistinct, but a possibility. I fix myself onto the couch outlooking to the window, where the ground is dotted with infant snow. I glimpse something in the corner of my eye. A snowflake falling towards the ground.

Gracefully. A possibility to be with others, to be loved. A possibility.

Lost. The only feeling I have ever known. Found. The only feeling I will ever know.

***

-

Shalina Effendi

Chiffon

By SHALINA EFFENDI

Grade: 12

IH Kempner HS, Fort Bend ISD

Teacher: Susan Henson

Silky, gauzy, gossamer-like strands. Woven with precise delicacy, chiffon is intentionally structured to be a lightweight fabric — but for the past five years, nothing has felt heavier on my head.

I felt its weight when I walked into Mr. Romero’s history class in 8th grade, wearing a hijab for the first time, only months after the Trump administration enacted “The Muslim Ban.” I felt it when the Smithsonian security guard singled me out for a “random security check.” But it has never felt heavier than the day I met my Pakistani mother's eyes in the Kroger checkout line while the cashier gave her a hard time, convinced a two-by-four-foot piece of cloth undermined her intelligence. In the mere milliseconds we shared a glance, I saw the guilt my mother felt for bringing us to a country where our faith was seen as a hazard. Moments like these reminded me of the ramifications of religious discrimination, even in a city as diverse as Houston.

That night, as we put the groceries away, my mother told me a story: When she moved here in 2007, halfway across the world from her hometown of Lahore, her hijab made her a target. In the aftermath of 9/11, she was defenseless against the constant slew of Islamophobic comments. Yet despite the hate she faced, she only ever responded with kindness.

“When you wear the hijab, you represent all of us, beta,” She reminds me.

My mother’s words are something I keep in mind every time I meet someone new. Amidst the backdrop of Houston’s diversity within a politically divided nation, my hijab offers me a window into the worlds of those unlike me. In a poverty-stricken neighborhood in the Southside, my mom and I serve homemade Biryani out of the trunk of her Ford Explorer. The residents come from every corner of the world. Sitting on the curb corner, I eat with Subira— a mother of three and refugee from Ethiopia. Though she’s Orthodox and I’m Muslim, a smile splits her weathered face when I talk about the significance of the hijab. She excitedly informs me about the veil that Ethiopian women wear. We talk for hours, about everything from the conflicts in Tigray and Kashmir to the struggle of practicing religion in the West, long after our food is finished.

It’s not always this simple, however. Canvassing for Lizzie Fletcher’s campaign, I meet Phil. Our political views are vastly different, and when he makes a comment about “Muslims tryin’ to infiltrate our country,'' I'm once again reminded that my hijab makes me a monolith. While I may have once viewed this as a disadvantage, it’s really an opportunity for me to represent my entire community. With my mother’s words in the back of my mind, I push past Phil’s preconceived notions and draw him into a rich conversation. Despite our pragmatic differences — his Bible Belt upbringing and my Islamic background — we find common ground in the fact that faith serves as a guiding principle in our lives. That day, I leave with more than just a promised vote for Representative Fletcher: a greater understanding of how my hijab can bridge ideological gaps.

It’s no secret that wearing a hijab is not easy: the gas station employee acting as if I don’t speak English, dirty looks from a shop owner as I enter the store, a teenage girl muttering “terrorist” under her breath as I walk by. But it’s also incredibly rewarding. My hijab offers me the courage to connect with others, whether they’re like me or not.

My heart is a tapestry stitched with varying fabrics, a collection of stories that remind me it’s not what I look like or how I dress that matters — my words and character are what ultimately leave a lasting impression on those around me. In moments like these, the weight of my hijab abates.

Chiffon feels like chiffon again.

-

Jamelle Apriliakova Mariano

Dear Seasons

By JAMELLE APRILIAKOVA MARIANO

Grade: 10

Alief Early College HS, Alief ISD

Teacher: Katrena Reese

Dear Winter, Dear Spring

Dear Reader,

The trees’ leaves alter from bright red to lone branches

Replaced with the crisp sound of lit sadlewood to ashes

The church bells, the happy cheer, the singing of “Rudolph the Red Nose Reindeer”

The letters people write

The way it wrapped the town in a blanket of white

Whilst in the midst of the holly, the air filled with a hint of melancholy

As the winter grew bitter and cold , it sang the song of loneliness

Yet you stand still as a single tear slides down your skin so sheerDear Reader,

Look through the kaleidoscope of yourself

When the times are harsh as ice

Don't dare to dance with an honest traitor

Don't take the risk and roll the dice

On a chess board with the twisted games of its creator

Run from the games children play by the fireplace

Set your foot outside and give yourself some spaceDear Reader,

Don’t fall like the snowflakes on your windowsill

When the cold morning air that brushes your face making the world stand still

Be the warmth in a room full of lies like the fireplace in a cold cabin

Stand like the pine trees you see from out the window

The trees that still stand through a storm of snow

As you walk through the trailway of footprints on a white floorDon’t forget, when you’re on your way back to close the door.

Nights were long and days were short

I wandered in the depths of my mind as woe filled the air of the cabin

Who thought that I’d be here listening to the wind by the light of the flame and fire of my dragons

A strawberry wine stain on my shirt, the window blinds filled with dirt

Cobwebs on the corner walls, I watch the window as the snowflakes fall

As you can see it’s all a facade, beyond this guidance is just a broken heart

For I have fallen like the snowflakes on my windowsill

The way my eyes crystalized tears as I stand there still

The pine trees weren’t even strong, in fact they were feeble

Outside was an angry snowstorm, more than just a tiny drizzle

But the snowman started melting from its head down to the floor

It seems like winter is gone, its time to close the door.Dear Reader,

As the cherry blossoms spring and the flowers start to bloom

The blue turns to green with its vibrant perfume

Changes from the colors to the ambience of the air

Has also brought changes to the breeze in your hair

As the moon pulled away, the tide lifted

To make the sky rain pink while the oceans driftedDear Reader,

Remember how after the harsh cold came a beautiful growth

From the lone branches withstood to the growth of the evergreen

The pastels that brush a lavender haze scene

Bloom like the flowers after a cold, harsh winter

Find yourself again like the moon lighting the darkest spring night

Let your inner nightingale sing your song and take its flight

But never lay in the flowerbed of promises you can’t keep

It was an understatement to say I was growing to a rose as beautiful as ever

But the thorns surround me as if I was defending myself so I can be more clever

And not to get hurt like frostbite in winter

After the spring, the sun started to rise in the far west center

I knew it was time to cut the thorns from the roses I wore.Dear Summer, Dear Fall

Dear Reader,

Sunsets and wine, blue ocean lines

Ice cream that melted under a hot orange sphere

Those birthday candles that wished you were here

Summer was bright, though it brought a feeling of hariaeth whilst the overly blissful

Yet the fear of an angel calling betrayal rings the back of your head in a manner so wistful

At least you were blinded by the oceans of their stare, despair, oh how you wanted to be thereDear Reader,

Don’t forget about the way the sun went down

Though the days are long, nights are short, don’t let that make you frown

Caress the sand that stood between the sea and land

Be the sun that makes the scene oh so grand

But don’t get trapped in the light of the day

For remember after a tick of a clock, night is a second away

Bury the hatchets of your past but keep a map of the marks and where they last

Your guiding light lit the tunnel of the mysteries in your head

The next second you close your eyes and your lying in bed

Seeing a world of the past that went by so fast

But remember that past is a place of reminiscence, not residence

Days grew longer, nights got shorter

while a summer midnight stroke when the moonlight hit the water

I sit in my thoughts as the warm bronze air whispered to me

“I’m about to go but I’ll be here next year

Find yourself to love as the seasons start to change

But don’t change the way how your waters ran through the coastline range”

Thinking to myself I found something, or someone that I can call love?

A self realization knowing my vices were the versa

That maybe I’ve enjoyed enough solitude

But the wine started spilling, my eyes started blinking

The tears of winter were back in a disguise

As an angel the brought me a surpriseDear Reader,

The last Aurora dawned like you before the clock rusted red

Your smile, your voice, the name I always call

Though it was sunburst and light, you still made me fall

Fall. Like the leaves that turned yellow and orange from bright green

A pile of leaves painted the hills vermillion

Cinnamon cookies, Burgundy scarves

Pumpkin spice lattes and pumpkin carves

Yet even with all this there was the thought of you

In a way I wasn’t sure if I felt joyful or blue

Oh well, I knew there was a reason the trees changed from green to a red hueDear Reader,

Like the fire in my heart as emotions heightened the atmosphere of chills

That leftover wine bloodshot red

There were books on the shelf that I never even read

But then again fall was on the small hand of the clock

And i truly fell like the leaves

That eventually faded away in the cold of the night

And that's when I knew. Winter was right.

Special Awards

-

Glassell Award

Lost in Thought by Katherine Xie | Grade: 10

Glenda Dawson High School, Pearland ISD

Educator: Teri Zuteck

Spring is Here by Hannah Wang | Grade: 9

Jeni Art Studio, Private Art School

Educator: Feng Zhu

Colorblind by Maria Marinescu | Grade: 11

Morton Ranch High School, Katy ISD

Educator: Laura Simoneaux

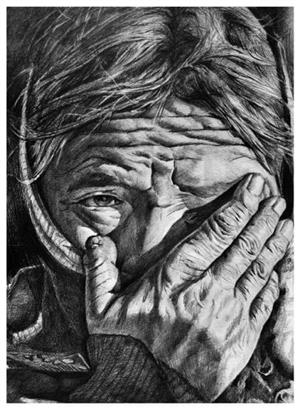

Old Woman by Danyeong Lee | Grade: 8

Stratford High School, Spring Branch ISD

Educator: Mao Li

Wannabe Models by Sophia Li | Grade: 8

Flux School of Art, Private Art School

Educator: Haoxiang Zhang

Small Hands, Big World by Zhuohan Liu | Grade: 8

Jeni Art Studio, Private Art School

Educator: Feng Zhu -

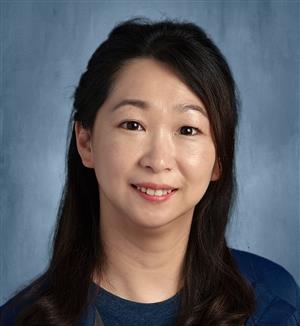

Susan O'Connor Award

Susan Henson

Susan Henson IH Kempner High School, Fort Bend ISD

A veteran secondary ELA teacher, Susan Henson has taught all levels of English, including Pre- AP and AP. Currently, she teaches AP Seminar and AP English Language and Composition at I.H. Kempner High School (Fort Bend ISD) in Sugar Land, Texas. With more than 20 years of experience, Henson specializes in AP English Language and Composition and has served as an AP reader and table leader for many years. Additionally, she authored a course guide, “Advanced Language” (2005), and has presented nationally on AP-related topics. In 2020, she received the Outstanding Teaching of the Humanities Award from Humanities Texas.

-

Blick Art Award

Kelly Chen

Clements High School, Fort Bend ISD

Fine Arts teacher Kelly Chen teaches a variety of classes at Clements High School in Sugar Land, Texas, including Art II, Art III, AP Drawing, AP 2D, Digital Art, and AP Art History. She is also the sponsor for the National Art Honor Society. Chen graduated from the University of Texas at Austin in 2006 with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Studio Arts with a specialization in drawing, painting, and photography and has been a teacher at Fort Bend ISD for 10 years.

-

Texas Art Supply Award

Divergent Manifest by Pamela Morales | Grade: 8

Schindewolf Intermediate School, Klein ISD

Educator: Samantha Lacey

Summertime Sass by Sophie Zhou | Grade: 9

Ping Zhao Art School, Private Art School

Educator: Ping Zhao

True North by Surrell Taylor | Grade: 12

Fort Bend Christian Academy-High School

Educator: Robert Sanders

On My Way by Lishan Bartlett-Will | Grade: 12

Carnegie Vanguard High School, Houston ISD

Educator: Rachel Bohenick

Loud and Clear by Lauren Oishi | Grade: 11

Glenda Dawson High School, Pearland ISD

Educator: Teri Zuteck -

Texas Art Supply Incentive Award

Impaired by Brady Teng | Grade: 12

Hanjie Arts Center, Private Art School

Educator: Haicun Weng

Delicates by Camila Barreiro | Grade: 11

Jordan High School, Katy ISD

Educator: Katrina Cerk

HCDE Awards

-

HCDE Trustees' Exemplary Award

Having OCD is like playing a never-ending game of Whac-A Mole. When one routine subsides, another swoops in to take its place. Aren’t carnival games rigged so the player always loses, anyways?

A Breakdown by Margot Kades | Grade: 12

St. John’s School, Private

Educator: Kyle Dennan

Plantas de los pies by Jasmine Zulaik | Grade: 10

Village High School, Private

Educator: Selene Bautista -

HCDE Trustees' Incentive Award

... the butterfly sparkled and darted with newfound strength and grace, unlike the limp moth it was before ... I found my own wings, unfurling, lifting me up in a swirl of sunset yellow. They pulsed with hues of orange and gold, shimmering with my love for music that would burn through the rest of my life.

Butterfly by Tiffany Zhang | Grade: 10

Kinkaid School, Private

Educator: Christa Forster

Blazing Novice by Alicia Clines | Grade: 11

Klein Cain High School, Klein ISD

Educator: Kaylee Hill -

HCDE Superintendent's Award

My wood is splintered and waning, but I have not been robbed of my courage

To connect the divided masses on either side of a rushing racial river

I am mixed race, and I am here to stay, I refuse to be disparaged

Because I Belong Here by Sophia Bellard

Grade: 10 | St Agnes Academy, Private

Educator: Herman Sutter

Better Days by Nisha Kalpathi | Grade: 9

William B. Travis High School, Fort Bend ISD

Educator: Natalie Albritton

-

See who won the 2023 regional awards!

The judges were impressed with student works submitted from our region. With over 7,700 art submissions and over 5,200 writing submissions, we are grateful for each student's participation.

Use the search tool on this page to search for a student, see all winners by school or district, and see this year's American Visions and Voices nominees.

Updated: Jan. 31, 2023

Contact Us

-

Center for Educator Success

Harris County Department of Education

6300 Irvington Blvd.

Houston, TX 77022

Phone: 713-696-8223Andrea Segraves

Scholastic Art & Writing Awards Regional Coordinator

EmailNorma Rodriguez

Professional Development Specialist

Email